|

|

ABOUT

SERVICES

PROJECTS

WRITING

CONTACT

|

Syntropic Agriculture Workshop at Gabalah Farm

October 2018 about thirty people convened on Scott Hall's Gabalah Farm for a workshop on Syntropic Agriculture (Agrofloresta). The workshop was led by Namastê Messerschmidt.

Below are my notes in case they are useful to anyone else. I wasn't trying to record everything, this is just anything which caught my attention in the moment and I could be bothered jotting down. Some of it's quite mundane, some very specific and lacking context, and some of it greatly helped my understanding of Syntropic methods and principals.

It's quite likely that I've understood things incompletely and may have reworded them poorly.

My uncurated collection of photos from the workshop is available.

When doing high apical cut on Eucalypts sometimes they resprout from the bottom. They’ve found that if you leave about 5 branches at the top that is enough to stop it resprouting at the base.

In arid/temperate climates you can use cactus or agave as alternative to banana (for chop and drop with lots of internal moisture).

Stratification is not height or longevity based, there are high strata short plants (eg. kale). If the plant is from a system with less resources (arid, cold, poor soil etc) than the entire system might be shorter.

Stratification is based on light requirements when the plant is mature (eg. a high strata plant will be tolerate additional shade for the first part of its life).

Corn and okra are emergent. Tomatoes and kales are high.

If they need full sun they are emergent. If they get sunburned they aren’t.

Broad, dark green leaves are an indication of lower layers.

The best way to know a plant is to live with it. Just like our mother, she can cut her hair or change clothes and we still know her.

From an ecological point of view you could have all four strata in a single organism. However to provide enough space for each layer, the high and emergent layers end up very tall and hard/dangerous to work with. In general they have found it is better to mix emergent and medium (or high and low) cropping species in a single row so your crops stay closer to the ground. You can have non-crop biomass emergent species mixed in as well.

You need 1-1.5m between the top of one strata and the bottom of the next. So if you have low strata to 2m then the bottom of your high strata can’t begin until 3.5m.

With these height requirements you can’t have high/emergent tree rows at 5m because you create too much shade. They’ve found it works well to alternate high/low rows with emergent/medium rows. That way there are 10m between your big trees.

When pruning you must respect strata and relationships between species. For example, if you prune a high species lower than a medium species it won’t thrive.

For simplicity of management it is best to have only one species of each strata in a single row.

Planning:

- What is going to make organic matter in short to long term?

- What to harvest when?

- Respect stratification and lifecycle

- Management considerations per species.

- How to sell harvests

- Plant sizes and spacing

- Type of organic matter (eg. tilth, what can germinate)

- Water

- Slope, sun & row orientation

- Machine or human labour resources

- Respect the vocation of the land/climate/season (grow what will thrive)

- Protection from animals

Start planning from the species which will remain in the system the longest (not counting biomass species) and work down through species that will be shorter lived.

Start planting from the biggest to the smallest, with seeds coming after seedlings and grafted plants. Idea is to make the most mess early so as few species as possible are disturbed by later planting.

Put grafting wound facing away from sun.

When planting trees cut off half of every leaf (in their experience this works better than cutting off every other leaf). Cut off all fruit/flowers for first two years to give tree a chance to establish. Grafted trees think they are older than they actually are and so you need to hold them back as producing even a few fruit takes a lot of effort for a young tree.

When planting root crops (cassava, taro, ginger etc) larger roots will produce larger crops because they have more stored energy to get started with.

Young, or sun sensitive plants, are more easily damaged by the afternoon sun. You can angle cuttings towards the west so less surface area is exposed to afternoon sun.

Don’t cut ginger for planting, break it with your fingers. Let the wound heal for about 5 days. Keeps it safer from infection. Not critical.

Grasses have all the same strata considerations (emergent, high, medium low).

Rule of thumb is that it takes 3m of grass to feed 1m of bed.

A consortium is an organism. If you introduce a new species mid-cycle their observation is that it won’t thrive. In order to introduce new species you either harvest the entire organism or create a “pulse” by heavily pruning everything in the row.

The boundaries between organisms aren’t distinct. A row is an organism, the inter-rows form an organism, the inter-rows plus the adjacent tree rows for an organism.

General recommendation was to treat the inter-rows as an organism and the tree rows as an organism.

When learning start small, 1sqm is great. Working first with short lived plants gives you lots of iterations to learn fairly quickly.

Plants will influence other plants in a radius equal to their height. So if you have a row senescent trees that are 10m tall, they will be slowing down the growth of other plants within a 10m radius.

In three sisters you strip the corn of leaves once the cob is fully formed (but not dried). This stops it sending senescence messages to other plants.

General rule is don’t plant a seed deeper than 4x it’s size. Shallower is better than too deep. Corn is an exception and can be planted deep and makes it stronger. Also can plant three corns together in same hole (like onions) with wider spacing for 20% shade.

Cannot cover grass seed with any organic matter or won’t germinate.

Building bamboo is typically high strata so could build a consortium with an emergent.

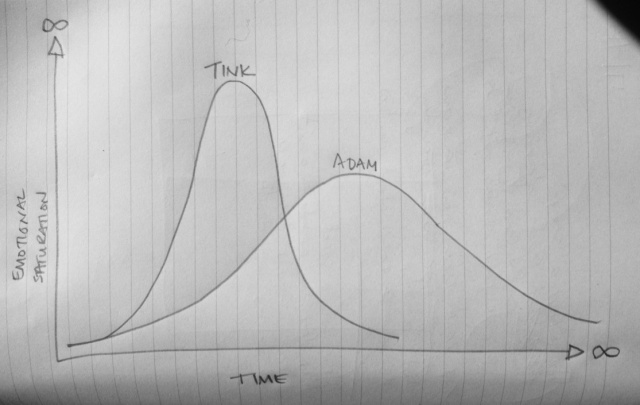

Every plant has a growth curve (x axis is time, y axis is biomass production). You want to prune as soon as the rate of biomass production starts dropping off. See photo for how senescence works with this.

They have observed that when planting lots of seeds at once, plants thrive. Plants seem to cooperate to make sure that a few thrive. Ernst says plant 100 seeds if you want one tree.

Seeds adapt to their environment, seedlings can struggle to adapt to the change after transplanting.

Make a slurry and dip tree seedlings into it to help with establishment. Use rock dust, ash or clay or whatever you have and is appropriate for that plant.

Horticulture beds do best on east side, so develop system with new beds being added to the east of what’s established.(Wonder if that’s the same in cooler climates?)

Bird seed can be a way to get untreated seeds.

They’ve observed that putting pruned organic matter on top of grass weeds doesn’t kill them, it makes them stronger. By pruning you are making light and then feeding them.

Prune biggest trees first. If you damage the smaller trees you still have options for how you prune.

On living wood, always use machete to cut in an upward angle (in the direction the plant fibres have grown). This creates a much cleaner cut then cutting downwards.

On dead wood, if you are holding the base of a limb, you chop in a downwards motion with the machete (same principal as above). It's less effort this ways.

Coppice on an angle, with cut surface facing south or east to minimise sun damage.

Diversity in organic material is important. More species is better.

They have observed that wood chip doesn’t create the same crumbly, black soil that diverse organic matter does. The finer “tilth” does make planting/sowing easier so sometimes is worth it.

When laying logs on soil it is important to cover them with organic matter or they seem to dry out and mummify rather the decompose.

When pruning citrus don’t prune a little off the tip of a branch, instead prune it back to just after a branch which can take over growth in the direction you want.

When creating a pulse any herbaceous plants which have completed their lifecycle (eg. flowering) can be cut because it won’t resprout. Then roots stay to nurture soil.

Producing some crops (seeds, fruit) will create a senescence effect. But it’s worth it if you want the crop.

You can’t compromise on organic matter. If you don’t have it you must grow it first.

Don’t sharpen the first third of your machete. Too easy to hurt yourself if your hand slips. Don’t use a machete two handed because if your blade side hand slips off you can cut yourself badly.

Trees don’t mind being pruned or even removed if it is in the best interests of the organism. Namaste said that we couldn’t think of trees like people (but I’m not sure that we are much different in this regard).

Once you have started a pulse you want to get everything planted fairly quickly so it can form an organism. Ideally you’d have it all done within a week.

Ernst says planting is 5% of the work, management is 95%.

Animals generally aren’t used within Syntropic systems. However some people were designing Syntropic systems specifically for chickens and egg production.

Questions:

- Nut crops and clear ground for harvesting. Perhaps grass rows next to trees? What about other plants within the tree row? Could you have berries which produce at a time that you could mow them after fruiting to harvest nuts?

- Trade offs on deciding which ways rows face? Lower latitudes? Colder climates? Wind? Slope?

- Would love more information on Syntropic chicken designs?

- How Ernst’s daughter felled the tree, with deep V cut?

- No mention of windbreaks which is unusual in tree systems. Is that because the entire system works as a windbreak?

- When pulsing a row to introduce a new species I’m unclear if coppicing the biomass species is sufficient to introduce new species? Or if you have to coppice “everything in the organism” (which wouldn’t work well with grafted trees).

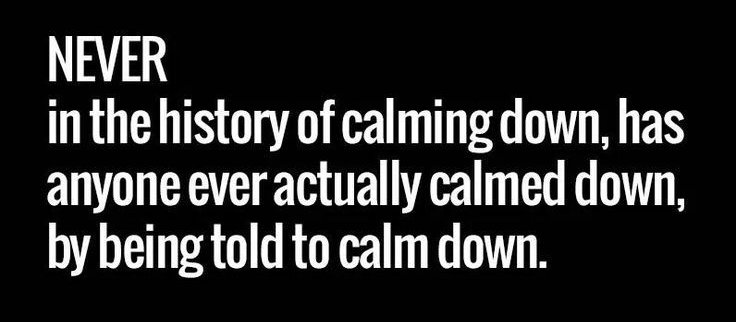

Never in the History of Calming Down …

First things first, this is funny! It’s funny because there’s truth in it, and based on how widely it was shared, it must be truth a lot of us can recognise!

I can’t read this without vivid memories of past arguments with girlfriends. While I was trying to figure out what was wrong and what I could do about it, she was this confusing, upsetting ball of emotions. I would get overwhelmed and frustrated (and eventually angry) because I didn’t really have any emotional tools to engage with her in a way which got me what I wanted (to understand what was wrong and what needed to be done about it).

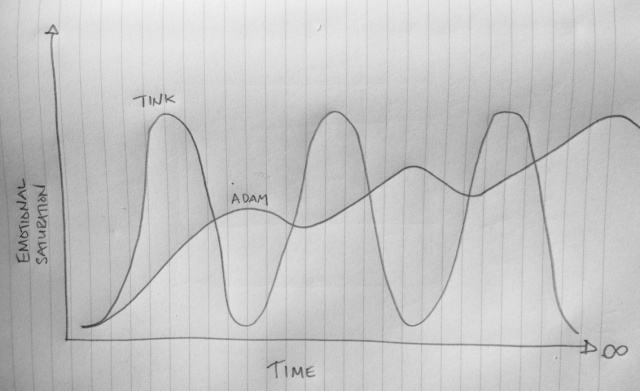

Even now after too many relationships, a career as a manager, a whole lot of spiritual work and plenty of time to reflect and practice; Tink can generate emotion faster than I can process it. She can go from happy, to upset, to angry, to crying and back to calm much faster than I can keep up. By the time she’s calm again, I’m still figuring out what made her angry, what she needs, how I feel about that, what I need and how to talk about it.

As long as we both remember this, it mostly works out. I hold her hand while she’s doing her thing, then she holds mine as I’m doing my thing, and then we work together to figure it out. For “extra credit”, sometimes we repeat this cycle a few times in the process of figuring it out.

Over longer periods this pattern can be more complicated. Early in our relationship, we (but especially Tink) went through a really tough patch. Because Tink could process emotion so much faster than me, by the time she needed to talk again, I was still only part way through processing our previous conversation. After a few months, my emotional bucket was constantly full and I started to get frustrated, and then angry when she tried to talk to me. I didn’t have room for any new emotion until I’d had a chance to process what was already in my bucket. Interestingly it was my anger which provided the clues I needed to figure it out.

Anger has been one of the big learnings in my life. The most important thing I have learned about my anger comes from Karla McLaren (summarised and interpreted by me, read the link if you want her version!):

I get angry when one of my boundaries is threatened.

With the anger comes the energy I need to take action.

If I use this energy to repair the boundary, my anger will go away.

Once I realised I was angry and had a chance to consider why I was feeling unsafe, I understood that my bucket was full and I needed a break to emotionally catch up. The hardest part was that I had to talk to Tink about this. At a time when she needed the most support, I had to tell her that actually, I couldn’t be there for everything. I felt like a failure and that I was betraying her trust. I had to ask anyway,“I understand that you need to talk and I want to be here to support you, but right now I’m really overwhelmed and need a break. Could you sometimes talk to a friend instead of me?”

None of this was as easy, as simple or as obvious as it sounds now. In fact, it was pretty messy, but we had the conversation and found a way that worked well enough for both of us. We got through the hard time.

Which in a roundabout way brings me back to where I started. Calming down.

In retrospect I understand that all those times when I was asking people to calm down, what I was trying to say was “please slow down, I can’t keep up”.

Learning to ask people important to me to calm down, in a way which is useful for both of us, has been a forty-two-year adventure.

Five Years

In December 2009 I quit my job at Weta Digital and headed off into the unknown. It was amazing. I spent a few months travelling aimlessly, a year studying yoga, a year living on permaculture farms, a year living on intentional communities and a year and half making a new home with Tink on her 12 acres on the Kāpiti Coast.

Today, today I signed a contract to go back to Weta Digital to help wrap up the hobbitses. So starting on Wednesday, and through to the end of October, I’ll be in town a lot more than I have been recently. The end of a movie isn’t the best time to plan a social life, but perhaps I’ll get to spend some more time with Wellington friends than I have in the last couple of years?

I am slightly embarrassed to announce this a week after Reece’s lovely video did the rounds, however financial reality has (finally) set in. My hope is that a short stint back in Miramar will get us through the quiet December/January period, pay off our credit cards and then life can go back to “normal” in 2015.

We’ve got plans for next year, and I’m looking forward to it!

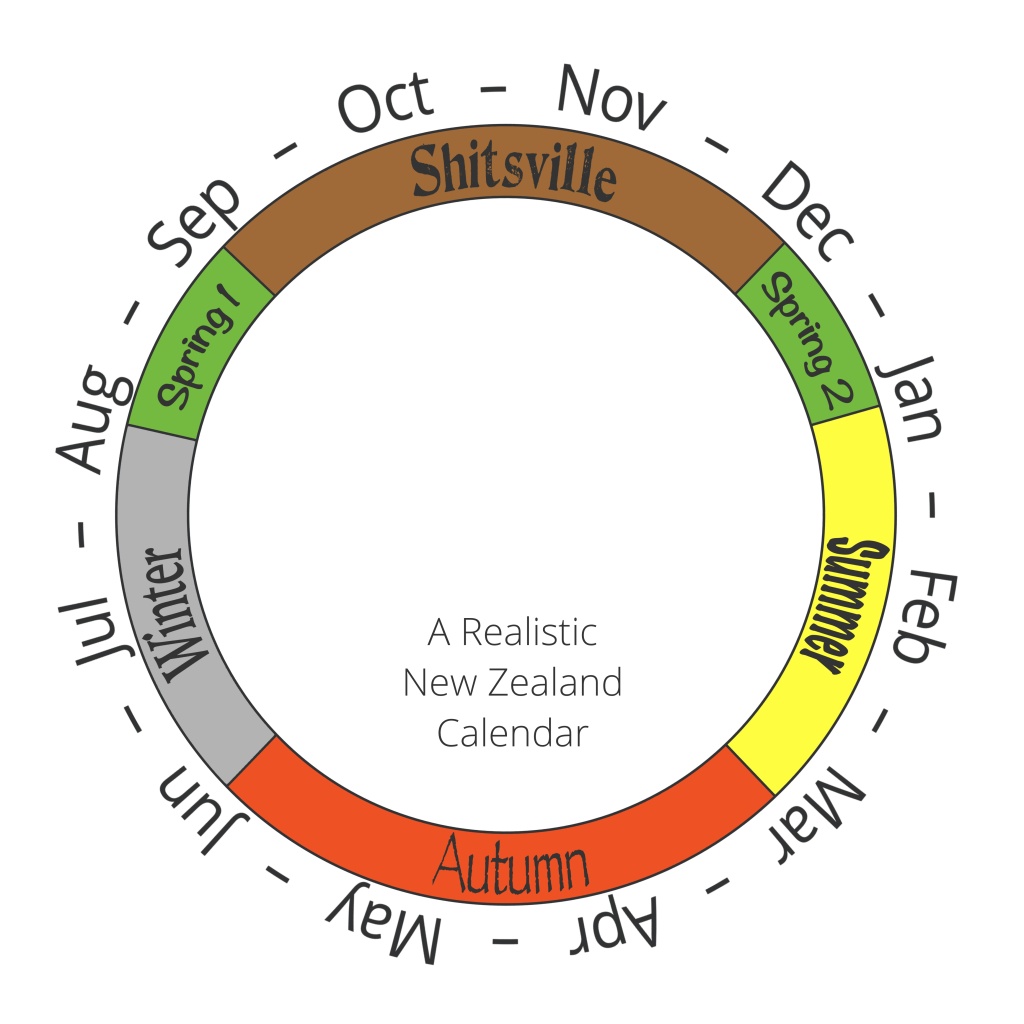

A Realistic Calendar for New Zealand

If you are new to New Zealand perhaps this calendar will help prepare you for the local progression of seasons.

I originally made this calendar specifically for Wellington, but it seems that much of New Zealand identifies with it so I renamed it.

Building a Cabin from a Shipping Container

People are talking about building tiny houses and cabins out of containers a lot recently. I built a cabin from a shipping container in 2012 to use as my primary (tiny) home. I only got it to fairly basic standards (basically an insulated box with two sets of doors) before the community I was living in collapsed and I moved out and sold it.

I’ve written my thoughts up for a couple of friends but have been meaning to do a better write up for ages. Here are the basic lessons I learned:

- Containers aren’t a particularly cheap way to build, but they are really fast. I got mine to it’s finished state with less than a weeks work (of about 1.5 people).

- It’s not particularly hard, but work with a builder if you can, they are amazingly fast.

- If you’re planning on living in it for the long haul, pay the extra for a hi-cube which gives you an extra 30cm of vertical space.

- There’s no way to know what the container was used to transport and some of them are used to transport seriously toxic shit.

- If you care about potential toxicity sandblast the steel walls and either cut out the plywood flour (not a very pleasant job) or investigate epoxy encapsulation of the floor.

- Containers are surprisingly expensive to move.

Overall I wouldn’t do it again unless for some reason I needed something fast and wanted to be able to sell it off fairly easily later. The research I did on toxicity didn’t leave me feeling comfortable, but I may be precious.

If I was going to build something like this again I would do it differently:

- If I wanted cheap I’d build with cob, earthbag or maybe straw bale.

- If I wanted super portable, I’d kit out a bus or caravan (extra annoying since I’m tall, but possible).

- If I wanted comfortable but easy to transport I’d get a yurt.1)

- If I wanted a transportable living space in or near a city I’d get a boat.

My analysis is that containers fall in the worst gaps of all of those. They aren’t particularly cheap, they aren’t particularly easy or cheap to move and they are potentially toxic.

One awesome thing you can do with containers is cantilever them. I have two designs that I’d love to build that would be super easy with containers … but over all I think it will be better to do it another way.

YMMV.

All I Want

“All I want in a relationship is for my partner to be able to tell me what she needs, and for it to be okay for me to say no sometimes.”

She looked at me. Like I’d just asked if she’d heard about the guy who was going to swim to the moon. “That’s all?”

“Well,” I said, “I also want to be able to ask for what I need, and know that she is able to say no.”

When did this become such a strange idea? That it is reasonable to expect each of us to ask for what we need. That we are able to respond honestly to any such request.

Asking for what we need might feel scary, embarrassing or selfish. Being asked to do something for someone can make us resentful, worried or anxious. Yet helping others is also a source of joy and can deepen our connection with the people around us.

Saying yes might mean weighing our needs for space or freedom against our desire to show affection or provide safety. Saying no may also involve weighing needs but also requires the courage to risk their frustration or pain. Hearing yes means trusting that the other person is agreeing to help us out of pleasure rather than fear. Hearing no requires the willingness to try and understand their needs and to explore alternatives.

All of which equals my sisters droll “is that all?”

Yet I can’t escape the sense that we’ve taken something simple and made it complicated. We all have the same needs; belonging, safety, joy, growth, beauty. Through our actions, however fumbling, each of us are each trying to find ways to meet those needs.

As we learn to look inward and see clearly what we need. As we gain skill with both speaking and hearing no. As we learn to trust the other people in our lives. As we gain confidence in our sense of self. We begin to come alive in each passing moment.

Laid out in front of me I see a path. A way that I hope will lead to a life of deeper and richer relationships. The beauty of this journey is that I don’t have to be skilled to begin. Each fumbling attempt carries me forward.

| ♡2014 by adam shand. sharing is an act of love, please share. | about · services · contact |